By Andrew Barron, Sêr Cymru Chair of Low Carbon Energy and Environment, Swansea University

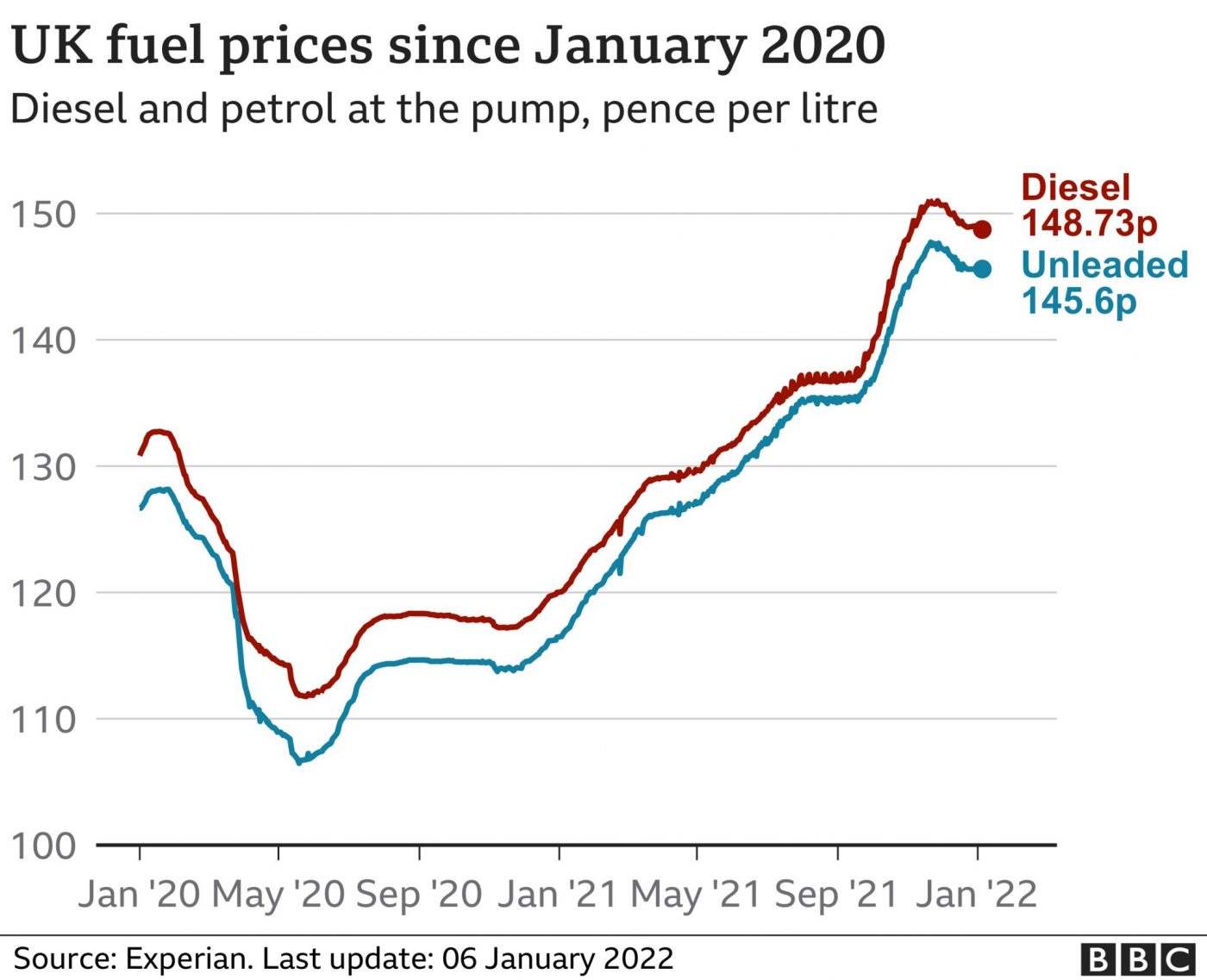

Across the UK the cost of filling up cars shot up in November when wholesale oil prices rose. But when crude oil prices went down again, costs at the pump did not drop back to previous levels. This has prompted UK motoring organisation, the RAC, to complain that drivers are being overcharged. So, what is going on?

Traditionally UK petrol prices have a strong relationship to the price of oil, but there has always been an asymmetry in how price changes are applied. While a rise in crude prices is passed on to the consumer within a month, cost reductions usually take somewhat longer to feed through to pump prices.

Although the average pump price has slowly inched down since late November, the decrease has not been as large as expected based upon the wholesale price. So, on this basis, it would appear that petrol station owners are taking advantage of the consumer. But is that the whole story?

How is the petrol price calculated?

The price that is paid for petrol at the pump is made of a number of factors. The largest portion is fuel duty (which is set at 57.95 pence a litre), this is followed by the cost of petrol itself, which includes the cost of the raw element (crude oil) and its refinement. Tax in the form of VAT (20 per cent) is applied to petrol purchases. These are all built in to the cost of petrol by the retailer. Profit has been traditionally about 5 per cent of the total price. Finally, the cost of delivery and distribution accounts for just under 2 per cent of the total cost.

If the cost of the petrol was the only factor in determining its price, then pump prices would track the wholesale price, but there is more to the business than that.

What is not included in the cost breakdown for petrol is the cost of running a petrol station, including wages for staff, electricity costs, rates and property costs. All of these have risen recently. The increase in the cost of operating a petrol station has also been exacerbated by a decrease in consumption.

Estimates show motor vehicles travelled about 16 er cent less than pre-pandemic levels. Miles driven went from around 9,200 miles in 2002 to 6,800 miles in 2020.

This is supported by data from the government’s business energy and industrial strategy, which reported that for most of December petrol sales volumes were running at 90 per cent of pre-pandemic levels and—for the week ending January 6—were at 60 per cent. Irrespective of the exact numbers, it is clear that less miles and therefore less fuel is being consumed.

There are other factors. Supplying just petrol to a motorist paying by credit card for example, can mean that the petrol station can also lose money on the transaction due to card charges. As a consequence, the majority of profit at a petrol station is not from the fuel but from the attached shop where the retail operation can generate a decent profit. The overall profitability of a retail petrol station is dependant more on the shop than petrol. So, pump prices could stay higher to make up for decreasing income from the shop.

As a consequence, with less foot traffic to the stores connected to petrol stations, but with certain fixed (and possibly increasing) costs such as electricity and wages, petrol retailers may have been forced to adjust pricing to ensure an overall profit.

A future for petrol stations?

So, the apparent decoupling of the wholesale and pump prices may signal an end to the pricing peculiarities that evolved in the UK due to price competition—going forward price changes may be more affected by profit margins. Whether this is just a kneejerk reaction or whether it’s going to be the new norm, only time will tell.

Nevertheless, these issues around profitability for petrol stations will be further tested with the ever-increasing percentage of electric vehicles (EVs) on UK roads. After all, if you “fill up” with electricity at home or work why do you need to stop at a small speciality store for supplies. You may just as well stop at a traditional grocery store or a smaller supermarket that will have a wider range of produce.

Those drivers not using EVs over the next few years are going to find changes in the cost of petrol since they will have to shoulder an increasing burden of the current business model for old-style petrol stations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation on January 12, 2022